ndian villagers queue outside a bank as they wait to deposit and exchange 500 and 1000 rupee notes in Hanuman Ganj village on the outskirts of Allahabad | Sanjay Kanojia/AFP

The Big Story: Fear and savings

“This tsunami will wipe out your money lying in the banks,” warned a message that went viral on WhatsApp recently, spreading panic among depositors. It was referring to the new Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill, 2017, lying with a joint parliamentary committee at present and expected to be tabled during the winter session. Among the more alarming features reported about the bill was a “bail in” clause that would apparently empower banks and regulators to dip into public deposits to rescue floundering financial institutions. The government has now gone into damage control mode, with Finance Minister Arun Jaitley clarifying that the bill would not compromise the rights of depositors, that it would in fact mean additional protections. But the panic comes at a time when public trust in institutions and financial systems is eroding.

Indian financial institutions are currently groaning under the massive weight of non–performing assets, created when banks lend to clients who default on payment. According to estimates put out in the Financial Stability Report of 2017, India has the second highest ratio of non-performing assets among the major economies of the world. The FRDI Bill is among the many measures planned by government to prop up failing banks. It proposes to set up a Resolution Corporation, which would monitor firms, calculate stress and take the appropriate “corrective action”. This body ensures that government would have a larger say in functions previously performed by the Reserve Bank of India and other financial regulators, which could signal another instalment in the turf war between the central bank and the Centre. It also proposes to do away with the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation, a subsidiary of the Reserve Bank of India created in 1971, which insures all kinds of bank deposits up to a limit of Rs 1 lakh.

The contentious “bail-in” clause, which involves the use of depositors’ funds to prop up flailing financial institutions, is in contrast to a bail out, where tax payers’ fund are injected into the system. It emerged as an alternative to the bail out after the financial crisis of 2008, when banks across the world went bust. This bill specifies that it would not apply to insured deposits and several other categories, which implies that the risk profile for ordinary depositors has not changed substantially. But the new bill, as it does away with the Rs 1 lakh limit, does not specify the quantum of deposits that would now be insured. It also formalises the risks associated with depositing money in banks.

While demonetisation had the public scrambling to the banks to ensure that the money they held in currency notes was not wiped out overnight, this bill makes depositors nervous about those very bank accounts. Demonetisation, argued economist Amartya Sen, “undermines bank accounts, it undermines notes, it undermines the entire economy of trust”. It also undermined the credibility of the Reserve Bank of India, which appeared to have toed a political line. That steady erosion of trust has not abated with subsequent financial decisions taken by government. Earlier this year, the implementation of the goods and services tax involved the imposition of a punitive tax regime that raised prices and squeezed small businesses. Later, a skittish government scaled down the tax rates on over 200 items. Given the shocks of the past year, the new bill looks like another piece of caprice from a government which cares little for the ordinary depositor. It has its work cut out in convincing the public otherwise.

The Big Scroll

Jency Jacob, in this article first published in Boomlive.in, takes a look at what we know so far about the bail in clause.

Punditry

- In the Indian Express, Upendra Baxi argues that a state of impunity continues for acts of torture, while lawmakers and courts look the other way.

- In the Hindu, Faizan Mustafa writes that declaring triple talaq a penal offence does not stand up to the first principles of jurisprudence.

- In the Telegraph, Manini Chatterjee has some advice for Rahul Gandhi.

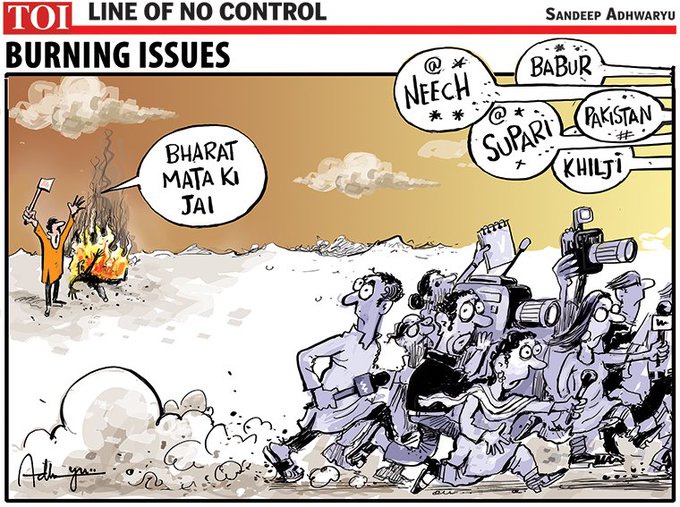

Giggles

Don’t miss…

Anjali Mody on why a British apology for the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre is superfluous:

Besides, the history of the empire is strewn with bodies. The question could be asked – why only Jallianwala Bagh?

After all, if we are talking massacres, the British colonial administration oversaw millions of starvation deaths from the 1860s onwards. These thoroughly avoidable deaths were the result of state policy. In years when there was sufficient rice to continue exports to Britain, colonial administrators ideologically wedded to the idea that market forces would solve the problem, that providing relief work promoted laziness, and the Malthusian theory that famines are a way of population control, caused millions to starve to death in eastern and southern India. Winston Churchill – who had excoriated Colonel Reginald Dyer, on whose orders soldiers had opened fire at the crowd in Jallianwala Bagh – pursued the same policy in 1943. Grain exports to Britain continued while over 3 million people died, most of them in Bengal.

[“Source-scroll.in”]