The retired firefighter, 53, needs Revlimid to stay healthy. Celgene Corp. has raised the price 88 percent over the past seven years. The drug doesn’t have substantial competition from a less expensive generic version, and probably won’t for another eight years. Celgene has worked hard to make sure of that.

Drugmakers typically have exclusive rights to sell brand-name medicines for 12 or 13 years. After that, cheaper copycats can hit the market. Celgene and a growing number of other pharmaceutical giants are taking advantage of an array of loopholes to extend the exclusivity period, keeping less expensive alternatives away from needy patients like Kelsey.

“Revlimid is the quintessential example of the way in which a pharmaceutical company can use a variety of tactics to extend their monopoly and then exploit that monopoly to increase revenues,” said Ameet Sarpatwari, a Harvard Medical School instructor.

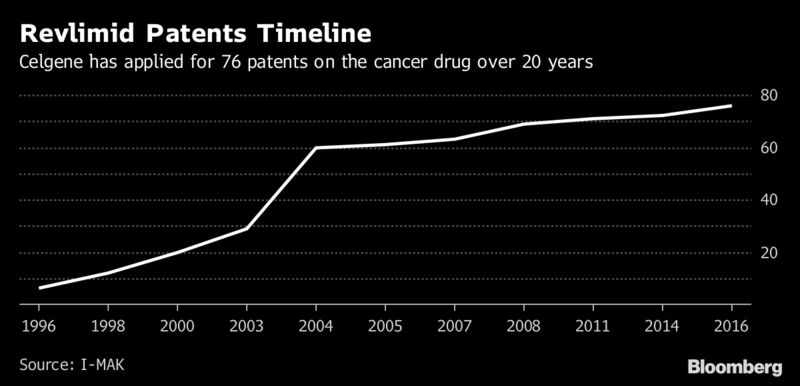

The expiration date for the main Revlimid patent will be 2019. But Celgene’s business tactics, also used by other drugmakers, could allow the company to put off unrestricted competition from generics until 2026. That would cost Americans an extra $45 billion just for Revlimid, according to I-MAK, a consumer advocate.

Scott Gottlieb, commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is so fed up with a range of different drugmakers’ machinations he delivered a sharp rebuke last month: “End the shenanigans.”

Among the shenanigans: Securing new patents that extend old ones. Keeping brand-name drugs under wraps so generic makers can’t copy them. Filing so-called citizen petitions that gum up the FDA approval process for rivals. Negotiating restrictive deals with drug plans that crowd out less expensive drugs.

Over the past year, Bloomberg has been looking into the price of pharmaceuticals, cataloging how drugmakers have been able to use a series of tactics to retain profits for years, undermining the deal they made more than three decades ago to allow generics on the market.

Celgene “has legitimate safety concerns” about generic companies’ use of its products, spokesman Brian Gill said in a statement. The company is “committed to helping patients access Revlimid” and has given aid to 75,000 people through its support program, Gill said.

The expectation of more exclusivity fuels investment in drug companies, potentially leading to future breakthroughs—even as some patients have trouble paying for the drugs, said Craig Garthwaite, a professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. “It’s just a fundamental tradeoff,” he said.

Under a 2015 deal with Celgene, one generic company will be allowed to sell generic Revlimid in 2022, although with restrictions on its market share.

Bob Kelsey used to stand 6 feet tall. His blood cancer has so weakened his spine that his back is bent at a sharp angle. He’s unable to completely lift his head. At last measurement, he was 5-foot-3.

He’s gotten so self-conscious about how he looks, he shied away from photos at his daughter’s wedding, according to his wife, Tammie.

But if his photo could help people afford medications, “he would pose for a thousand pictures,” Tammie Kelsey said.

Bob Kelsey said Celgene is providing him with free doses until a charity comes through for him. But even if he does get the grant, he’s worried the money won’t last a year and he’ll have to reapply elsewhere.

Revlimid is $662 a capsule, and it can come to $180,000 a year. Celgene spent $800 million on research and development for all its products over the 14 years it prepared Revlimid for sale, regulatory filings show. The drug exceeded $1 billion in annual sales in 2008, its third full year on the market, and last year had sales of $6.97 billion.

Today, a year’s worth of 10-milligram Revlimid doses costs about $240 to produce, according to a University of Liverpool researcher. Under Kelsey’s Medicare plan, his annual out-of-pocket cost would be more than $10,000, too steep for him to pay.

“I want to be here to see my grandchildren,” he said.