The myth that online education courses cost less to produce and therefore save students money on tuition doesn’t hold up to scrutiny, a survey of distance education providers found.

The survey, conducted by the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies (WCET), found that most colleges charge students the same or more to study online. And when additional fees are included, more than half of distance education students pay more than do those in brick-and-mortar classrooms.

The higher prices — what students pay — are connected to higher production costs, the survey found. Researchers asked respondents to think about 21 components of an online course, such as faculty development, instructional design and student assessment, and how the cost of those components compares to a similar face-to-face course. The respondents — administrators in charge of distance education at 197 colleges — said nine of the components cost more in an online course than in a face-to-face course, while 12 cost about the same.

More Coverage of Online Learning

If you’re interested in these and

other issues, sign up for Inside Digital

Learning, our new weekly publication.

All original news, opinion and other

content. Subscribe here.

In other words, virtually every administrator surveyed said online courses are more expensive to produce.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise, according to Russell Poulin and Terri Taylor Straut, the authors of the study. Producing an online course means licensing software, engaging instructional designers, training faculty members and offering around-the-clock student support, among other added costs, they point out in the report.

“And all this is supposed to cost less?” the report reads. “In the open-ended comments addressing leaders who criticize their work, you can feel their pain. As one person succinctly responded to those critics: ‘Nuts.’”

In an interview, Straut, senior research analyst at WCET, said the myth about the lower cost and price of online education persists because of a lack of knowledge about the work that goes into creating the courses. Rather than building online courses from scratch, many colleges have used a “bolt-on” approach that starts off with taking the face-to-face course and adding the tools needed to offer it online, which drives up costs, she said.

“If you start with all the pieces in the classroom and then add on technology, how could that possibly be cheaper?” said Straut, who previously helped found CU Online, at the University of Colorado, and Western Governors University.

Additionally, Straut said, colleges have mainly focused on online education as a way to further their missions of increasing access to education, not lowering costs.

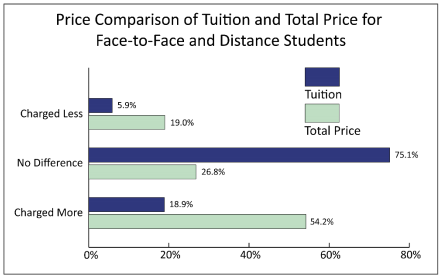

The differences in which fees students pay may help explain why only 5.9 percent of respondents said students who study online pay less for tuition than do those who study in person, compared to the 19 percent who said the total price — tuition and fees — is lower for online students.

But the difference is greater on the other end of the scale. Looking at tuition alone, 18.9 percent of respondents said those rates are higher for online students, but that share jumped to 54.2 percent when fees were added.

The added technology costs mean that many students in online three-credit courses pay up to $100 (32.9 percent) or between $101 and $250 (12 percent) more in fees than students do in similar face-to-face courses.

Colleges — particularly public institutions — generally have more control over the fees they charge than over tuition rates. More than twice as many respondents said the state Legislature is involved in the approval process for setting tuition rates (17 percent) than fee rates (8.1 percent).

The University of Florida, which is referenced in the report, is one example. State legislators in 2013 mandated that the university could charge online students no more than 75 percent of on-campus tuition rates. In-state online students at UF pay $17.26 in fees per credit hour (including a financial aid fee, technology fee and capital improvement fee). Out-of-state students are charged an additional $35.36 non-Florida resident financial aid fee per credit hour.

The authors said they hope the study will inspire conversations among college officials and politicians about the cost and price of higher education.

“If the goal is to cut costs while maintaining quality and access, we must think differently at a structural level so that quality, affordable options for students are assured,” the report reads. “Goal setting and rethinking existing structures are key.”

[Source:-Inside Higher ED]